Scotland

FREE Catholic Classes

The term as at present used includes the whole northern portion of the Island of Great Britain, which is divided from England by the Cheviot Hills, the River Tweed, and certain smaller streams. Its total area is about 20,000,000 acres, or something over 30,000 square miles; its greatest length is 292 miles, and greatest breadth, 155 miles. The chief physical feature of the country is its mountainous character, there being no extensive areas of level ground, as in England ; and only about a quarter of the total acreage is cultivated. The principal chain of mountains is the Grampian range, and the highest individual hill Ben Nevis (4406 feet). Valuable coalfields extend almost uninterruptedly from east to west, on both banks of the Rivers Forth and Clyde. The climate is considerably colder and (except on parts of the east coast) wetter than that of England. The part of Scotland lying beyond the Firths of Forth and Clyde was known to the Romans as Caledonia. The Caledonians came later to be called Picts, and the country, after them, Pictland. The name of Scotland came into use in the eleventh century, when the race of Scots, originally an Irish colony which settled in the western Highlands, attained to supreme power in the country. Scotland was an independent kingdom until James VI succeeded to the English Crown in 1603; and it continued constitutionally separate from England until the conclusion of the treaty of union a century later. It still retains its own Church and its own form of legal procedure; and the character of its people remains in many respects quite distinct from that of the English. Formerly the three prevailing nationalities of the country were the Anglo-Saxon in the south, the Celtic in the north and west, and the Scandinavian in the north-east; and these distinctions can still be traced both in the characteristics of the inhabitants and in the proper names of places. The total population, according to the census Of 1911 is 4,759,521, being an increase of 287,418 in the past decade. The increase is almost entirely in the large cities and towns, the rural population of almost every county, except in the mining districts, having sensibly diminished, owing to emigration and other causes, since 1901.

The history of Scotland is dealt with in the present article chiefly in its ecclesiastical aspect, and as such it naturally falls into three great divisions: I. The conversion of the country and the prevalence of the Celtic monastic church; II. The gradual introduction and, consolidation of the diocesan system, and the history of Scottish Catholicism down to the religious revolution of the sixteenth century; III. The post-Reformation history of the country, particularly in connection with the persecuted remnant of Catholics, and finally the religious revival of the nineteenth century. Under these three several heads, therefore, the subject will be treated.

I. FIRST PERIOD: FOURTH TO ELEVENTH CENTURY

Nothing certain is known as to the introduction of Christianity into Scotland prior to the fourth century. Tertullian, writing at the end of the second, speaks of portions of Britain which the Romans had never reached being; by that time "subject to Christ"; and early Scots historians relate that Pope Victor, about A.D. 203, sent missionaries to Scotland. This pope's name is singled out for special veneration in a very, early Scottish (Culdee) litany, which gives some probability to the legend; but the earliest indubitable evidence of the religious connection of Scotland with Rome is afforded by the history of Ninian, who, born in the south-west of Scotland about 360, went to study at Rome, was consecrated bishop by Pope Siricius , returned to his native country about 402, and built at Candida Casa, now Whithorn, the first stone church in Scotland. He also founded there a famous monastery, whence saints and missionaries went out to preach; not only through the whole south of Scotland, but also in Ireland. Ninian died probably in 432; and current ecclesiastical tradition points to St. Palladius as having been his successor in the work of evangelizing Scotland. Pope Leo XIII cited this tradition in his Bull restoring the Scottish hierarchy in 1878; but there are many anachronisms and other difficulties in the long-accepted story of St. Palladius and his immediate followers, and it is even uncertain whether he ever set foot in Scotland at all. If, however, his mission was to the Scoti , who at this period inhabited Ireland, he was at least indirectly connected with the conversion of Scotland also; for the earliest extant chronicles of the Picts show us how close was the connection between the Church of the southern Picts and that of Ireland founded by St. Patrick. In the sixth century three Irish brother-chieftains crossed over from Ireland and founded the little Kingdom of Dalriada, in the present County of Argyll, which was ultimately to develop into the Kingdom of Scotland. They were already Christians, and with them came Irish missionaries, who spread the Faith throughout the western parts of the country. The north was still pagan, and even in the partly Christianized districts there were many relapses and apostasies which called for a stricter system of organization and discipline among the missionaries. It was thus that, drawing her inspiration from the great monasteries of Ireland, the early Scottish Church entered upon the monastic period of her history, of which the first and the greatest light was Columba, Apostle of the northern Picts.

The monastery of Iona, where Columba settled in 563, and whence he carried on his work of evangelizing the mainland of Scotland for thirty-four years, was, under him and his successors in the abbatial dignity, considered the mother-house of all monasteries founded by him in Scotland and in Ireland. Bede mentions that Iona long held pre-eminence over all the monasteries of the Picts, and it continued in fact, all during the monastic period of the Scottish Church, to be the centre of the Columban jurisdiction. It is unnecessary to argue the point, which has been proved over and over again against the views put forward both by Anglicans and Presbyterians, that the Columban church was no isolated fragment of Christendom, but was united in faith and worship and spiritual life with the universal Catholic Church (see as to this, Edmonds, "The Early Scottish Church, its Doctrine and Discipline", Edinburgh, 1906). Whilst Columba was labouring among the northern Picts, another apostle was raised up in the person of St. Kentigern , to work among the British inhabitants of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, extending southward from the Clyde to Cumberland. Kentigern may be called the founder of the Church of Cumbria, and became the first bishop of what is now Glasgow ; while in the east of Scotland Lothian honours as its first apostle the great St. Cuthbert, who entered the monastery of Melrose in 650, and became bishop, with his see at Lindisfarne, in 684. He died three years later; and less than thirty years afterwards the monastic period of the Scottish Church came to an end, the monks throughout Pictland, most of whom had resisted the adoption of the Roman observance of Easter, being expelled by the Pictish king. This was in 717, and almost simultaneously with the disappearance of the Columban monks we see the advent to Scotland of the Deicolae, Colidei or Culdees , the anchorite-clerics sprung from those ascetics who had devoted themselves to the service of God in the solitude of separate cells, and had in the course of time formed themselves into communities of anchorites or hermits. They had thirteen monasteries in Scotland, and together with the secular clergy who were now introduced into the country they carried on the work of evangelization which had been done by the Columban communities which they succeeded.

From the beginning of the eighth to the middle of the ninth century the political history of Scotland, as we dimly see it today, consists of continual fighting between the rival races of Angles, Picts, and Scots, varied by invasions of Danes and Norsemen, and culminating at last in the union of the Scots of Dalriada and the Pictish peoples into one kingdom under Kenneth Mac Alpine in 844. Ecclesiastically speaking, the most important result of this union was elevation by Kenneth of the church of Dunkeld to be the primatial see of his new kingdom. Soon, however, the primacy was transferred to Abernethy, and some forty years after Kenneth's accession we find the first definite mention of the "Scottish Church ", which King Grig raised from a position of servitude to honourable independence. Grig's successors were styled no longer Kings of the Picts, but Kings of Alban, the name now given to the whole country between forth and the Spey; and under Constantine, second King of Alban, was held in 908 the memorable assembly at Scone, in which the king and Cellach, Bishop of St. Andrews, recognized by this time as primate of the kingdom, and styled Epscop Alban, solemnly swore to protect the discipline of the Faith and the right of the churches and the Gospel. In the reign of Malcolm I, Constantine's successor, the district of Cumberland was ceded to the Scottish Crown by Edmund of England ; and among the very scanty notices of ecclesiastical affairs during this period we find the foundation of the church of Brechin of which the ancient round tower, built after the Irish model, still remains. This was in the reign of Kenneth II (971-995), who added yet another province to the Scottish Kingdom, Lothian being made over to him by King Edmund of England. Iona had meanwhile, in consequence of the occupation of the Western Isles by the Norsemen, been practically cut off from Scotland, and had become ecclesiastically dependent on Ireland. It suffered much from repeated Danish raids, and on Christmas Eve, 986, the abbey was devastated, and the abbot with most of his monks put to death . Not many years later the Norwegian power in Scotland received a fatal blow by the death of Sigurd, Earl of I Orkney, the Norwegian provinces on the mainland passing into the possession of the Scottish Crown. Malcolm II was now on the throne, and it was during his thirty years' reign that the Kingdom of Alban became first known as Scotia, from the dominant race to which its people belonged. With Malcolm's death in 1034 the male line of Kenneth Mac Alpine was extinguished, and he was succeeded by his daughter's son, Duncan, who after a short and inglorious reign was murdered by his kinsman and principal general, Macbeth. Macbeth wore his usurped crown for seventeen years, and was himself slain in 1057 by Malcolm, Duncan's son, who ascended the throne as Malcolm III. It is worth noting that Duncan's father (who married the daughter of Malcolm II) was Crinan, lay Abbot of Dunkeld ; for this fact illustrates one of the great evils under which the Scottish Church was at this time labouring, namely the usurpation of abbeys and benefices by great secular chieftains, an abuse existing side by side, and closely connected with, the scandal of concubinage among the clergy, with its inevitable consequence, the hereditary succession to benefices, and wholesale secularization of the property of the Church. These evils were indeed rife in other parts of Christendom ; but Scotland was especially affected by them, owing to her want of a proper ecclesiastical constitution and a normal ecclesiastical government. The accession, and more especially the marriage, of Malcolm III were events destined to have a profound influence on the fortunes of the Scottish Church, and indeed to be a turning-point in her history.

II. SECOND PERIOD: ELEVENTH TO SIXTEENTH CENTURY

The Norman Conquest of England could not fail to exercise a deep and lasting effect also on the northern kingdom, and it was the immediate cause of the introduction of English ideas and English civilization into Scotland. The flight to Scotland, after the battle of Hastings, of Edgar Atheling, heir of the Saxon Royal house, with his mother and his sisters Margaret and Christina, was followed at no great distant date by the marriage of Margaret to King Malcolm, as his second wife. A greatniece of St. Edward the Confessor , Margaret, whose personality stands out clearly before us in the pages of her biography by her confessor Turgot, was a woman not only of saintly life but of strong character who exercised the strongest influence on the Scottish Church and kingdom, as well as on the members of her own family. The character of Malcolm III has been depicted in very different colours by the English and Scottish chroniclers, the former painting him as the severe and merciless invader of England, while to the latter he is a noble and heroic prince, called Canmore ( Ceann-mor great head) from his high kingly qualities. All however agree that the influence of his holy queen was the best and strongest element in his stormy life. Whilst he was engaged in strengthening his frontiers and fighting the enemies of his country, Margaret found time, amid family duties and pious exercises, to take in hand the reform of certain outstanding abuses in the Scottish Church. In such matters as the fast of Lent, the Easter communion, the observance of Sunday, and compliance with the Church's marriage laws she succeeded, with the king's support, in bringing the Church of Scotland into line with the rest of Catholic Christendom. Malcolm and Margaret rebuilt the venerable monastery of Iona, and founded churches in various parts of the kingdom; and during their reign the Christian faith was established in the islands lying off the northern and western coasts of Scotland, inhabited by Norsemen. Malcolm was killed in Northumberland in 1093, whilst leading an army against William Rufus; and his saintly queen, already dangerously ill, followed him to the grave a few days later. In the same year as the king and queen died Fothad, the last of the native bishops of Alban, whose extinction opened the way to the claim, long upheld, of the See of York to supremacy over the Scottish Church — a claim rendered more tenable by the strong Anglo-Norman influence which had taken the place of that of Ireland, and by the absence of any organized system of diocesan jurisdiction in the Scottish Church.

Edgar, one of Malcolm's younger sons, who succeeded to his father's crown after prolonged conflict with other pretenders to it, calls himself in his extant charters "King of Scots", but he speaks of his subjects as Scots and English, surrounded himself with English advisers, acknowledged William of England as his feudal superior, and thus did much to strengthen the English influence in the northern kingdom. During his ten years' reign no successor was appointed to Fothad in the primacy ; but at his death (when his brother Alexander succeeded him as king, the younger brother David obtaining dominion over Cumbria and Lothian, with the title of earl) Turgot became Bishop of St. Andrews, the first Norman to occupy the primatial see. Alexander's reign was signalized by the creation of two additional sees ; the first being that of Moray, in the district beyond the Spey, where Scandinavian influence had long been dominant. The see was fixed first at Spynie and later at Elgin, where a noble cathedral was founded in the thirteenth century. The other new see was that of Dunkeld, which had already been the seat of the primacy under Kenneth Mac Alpine, but had fallen under lay abbots. Here Alexander replaced the Culdee community by a bishop and chapter of secular canons. Elsewhere also he introduced regular religious orders to take the place of the Culdees, founding monasteries of canons regular (Augustinians) at Scone and Loch Tay.

Even more than Alexander, his brother David, who succeeded him in 1124, and who had been educated at the English Court (his sister Matilda having married Henry I), laboured to assimilate the social state and institutions of Scotland, both in civil and ecclesiastical matters, to Anglo-Norman ideas. His reign of thirty years, on the whole a peaceful one, is memorable in the extent of the changes wrought during it in Scotland, under every aspect of the life of the people. A modern historian has said that at no period of her history has Scotland ever stood relatively so high in the scale of nations as during the reign of this excellent monarch. Penetrated with the spirit of feudalism, and recognizing the inadequacy of the Celtic institutions of the past to meet the growing needs of his people, David extended his reforms to every department of civil life; but it is with the energy and thoroughness with which he set about the reorganization and remodelling of the national church that his name will always be identified. While still Earl of Cumbria and Lothian he brought Benedictine monks from France to Selkirk, and Augustinian canons to Jedburgh, and procured the restoration of the ancient see of Glasgow, originally founded by St. Kentigern. Five other bishoprics he founded after his accession : Ross, in early days a Columban monastery, and afterwards served by Culdees, who were now succeeded by secular canons; Aberdeen, where there had also been a church in very early times; Caithness, with the see at Dornoch, in Sutherland, where the former Culdee community was now replaced by a full chapter of ten canons, with dean, precentor, chancellor, treasurer, and archdeacon ; Dunblane, and Brechin, founded shortly before the king's death, and both, like the rest, on the sites of ancient Celtic churches, The great abbeys of Dunfermline, Holyrood, Jedburgh, Kelso, Kinloss, Melrose, and Dundrennan were all established by him for Benedictines, Augustinians, or Cistercians, besides several priories and convents of nuns, and houses belonging to the military orders. To one venerable Celtic monastery, founded by St. Columba, that of Deer, we find David granting a charter towards the end of his reign; but his general policy was to suppress the ancient Culdee establishments, now moribund and almost extinct, and supersede them by his new religious foundations. Side by side with this came the complete diocesan reorganization of the Church, the erection of cathedral chapters and rural deaneries, and the reform of the Divine service on the model of that prevailing in the English Church, the use of the ancient Celtic ritual being almost universally discontinued in favour of that of Salisbury. Two church councils were held in David's reign, both presided over by cardinal legates from Rome ; and in 1150 took place, at St. Andrews, the first diocesan synod recorded to have been held in Scotland. David died in 1153, leaving behind him the reputation of a saint as well as a great king, a reputation which has been endorsed, with singular unanimity, alike by ancient chroniclers and the most impartial of modern historians.

David's grandson and successor, Malcolm the Maiden, was crowned at Scone — the first occasion, as far as we know, of such a ceremony taking place in Scotland. His piety was attested by his many religious foundations, including the famous Abbey of Paisley; but as a king he was weak, whereas England was at that time ruled by the strong and masterful Henry II, who succeeded in wresting from Scotland the three northern English counties which had been subject to David. Malcolm was succeeded in 1165 by his brother William the Lion, whose reign of close on fifty years was the longest in Scottish history. It was by no means a period of peace for the Scottish realm; for in 1173 William, in a vain effort to recover his lost English provinces, was taken prisoner, and only released on binding himself, to be the liegerman of the King of England, and to do him homage for his whole kingdom. During a great part of his reign he was also in conflict with his unruly Celtic subjects in Galloway and elsewhere, as well as with the Norsemen of Caithness. The Scottish Church, too, was harassed not only by the continual claims of York to jurisdiction over her, but by the English king's attempts to bring her into entire subjection to the Church of England. A great council at Northampton in 1176, attended by both monarchs, a papal legate , and the principal English and Scottish bishops, broke up without deciding this question; and a special legate sent by Pope Alexander III to England and Scotland shortly afterwards was not more successful.

It was not until twelve years later that, in response to a deputation specially sent to Rome by William to urge a settlement, Pope Clement III (in March, 1188) declared by Bull the Scottish Church, with its nine diocese, to be immediately subject — to the Apostolic See. The issue of this Bull, which was confirmed by succeeding popes, was followed, on William subscribing handsomely to Richard Coeur de Lion's crusading fund, by the King of England agreeing to abrogate the humiliating treaty which had made him the feudal of superior of the King of Scots, and formally recognizing the temporal, as well as the spiritual independence of Scotland. William's reign, like that of its predecessors, was prolific in religious foundations, the principal being the great Abbé of Arbroath, a memorial of St. Thomas of Canterbury, with whom the king had been on terms of personal friendship. Even more noteworthy was the establishment of a Benedictine monastery in the sacred Isle of Iona by Reginald, Lord of the isles, whose desire, like that of the Scottish kings was to supersede the effete Culdees in his domains by the regular orders of the Church. In 1200 a tenth diocese was erected — that of Argyll, cut off from Dunkeld, and including an extensive territory in which Gaelic was (as it still is) almost exclusively spoken. The Fourth Lateran Council was held in Rome in 1215, the year-after William's death, under the great Pope Innocent III , and was attended by four Scottish bishops and abbots, and procurators of the other prelates ; and we fin& the ecclesiastics of Scotland, as of other countries, ordered to contribute a twentieth part of their revenues towards a new crusade, and a papal legate arriving to collect the money. In 1225 the Scottish bishops met in council for the first time without the presence of a legate from Rome, electing one of their number, as directed by with a papal bull, to preside over the assembly with quasi-metropolitan authority and the title of conservator. The Scottish kings were regularly represented at these councils by two doctors of laws specially nominated by the sovereign.

The thirteenth century, during the greater part of which (1214-86) the second and third Alexanders wore the crown of Scotland, is sometimes spoken of as the golden age of that country. During that long period, in the words of a modern poet, " God gave them peace, their land reposed"; and they were free to carry on the work of consolidation and development so well begun by the good King David II. Alexander II, indeed, when still a youth incurred the papal excommunication by espousing the cause of the English barons against King John, but when he had obtained absolution he married a sister of Henry III , and so secured a good understanding with England, The occasional signs of unrest among some of his Celtic subjects in Argyll, Moray, and Caithness were met and checked with firmness and success; and this reign with a distinct advance in the industrial progress of the realm, the king devoting special attention to the improvement of agriculture. Many new religious foundations were also made by him, including monasteries at Culross, Pluscardine, Beuly, and Crossraguel; while the royal favour was also extended to the new orders of friars which were spreading throughout Europe, and numerous houses were founded by him both for Dominicans and Franciscans, the friars, however, remaining under the control of their English provincials until nearly a century later. David de Bernham of St. Andrews and Gilbert of Caithness were among the distinguished prelates of this time, and did much for both the material and religious welfare of their dioceses. Alexander III, who succeeded his father in 1249, was also fortunate in the excellent bishops who governed the Scottish Church during his reign, and he, like his predecessors, made some notable religious foundations, including the Cistercian Abbey of Sweetheart, and houses of Carmelite and Trinitarian friars. An important step in the consolidation of the kingdom was the annexation of the Isle of Man, the Hebrides, and other western islands to the Scottish Crown, pecuniary compensation being paid to Norway, and the Archbishop of Trondhjem retaining ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the islands. Nearly all the Scottish bishops attended the general council convoked by Gregory X at Lyons in 1274, which, among other measures levied a fresh tax on chur ch benefices in aid of a new crusade. Boiamund, a Piedmontese canon, went to Scotland to collect the subsidy, assessing the clergy on a valuation known as Boiamund's Roll, which gave great dissatisfaction but nevertheless remained the guide to ecclesiastical taxation until the Reformation. With the death of Alexander in 1286 the male line of his house came to an end, and he was succeeded by his youthful granddaughter, Margaret, daughter of King Eric of Norway.

Edward I, the powerful and ambitious King of England, whose hope was the union of the Kingdom of Scotland with his own, immediately began negotiations for the marriage of Margaret to his son. The proposal was favourably received in Scotland; but while the eight-year-old queen was on her way from Orkney, and the realm was immediately divided by rival claimants to the throne, John de Baliol and Robert Bruce, both descended from a brother of William the Lion. King Edward, chosen as umpire in the dispute, decided in favour of Baliol; and relying on his subservience summoned him to support him when he declared war on France in 1294. The Scottish parliament, however entered instead into an alliance with France against England, whose incensed king at once marched into Scotland with a powerful army, advanced as far as Perth, dethroned and degraded Baliol, and returned to England, carrying with him from Scone the coronation stone of the Scottish kings, which he placed in Westminster Abbey, where it still remains. The interposition of Pope Boniface VIII procured a temporary truce between the two countries in 1300; but Edward soon renewed his efforts to subdue the Scotch, putting to death the valiant and patriotic William Wallace, and leaving no stone unturned to carry out his object. He died, however, in 1307; and Robert Bruce (grandson of Baliol's rival) utterly routed the English forces at Bannockburn in 1314, and secured the independence of Scotland. After long negotiations peace was concluded between the two kingdoms, and ratified by the betrothal of Robert's only son to the sister of the King of England. Robert died a few months later, and was succeeded by his son, David II, out of whose reign of forty years ten were spent, during his youth, in France, and eleven in exile in England, where he was taken prisoner when invading the dominions of Edward III. During the wars with England, and the long and inglorious reign of David, the church and people suffered alike. Bishops forgot their sacred character, and appeared in armour at the head of their retainers; the state of both of clergy and laity, was far from satisfactory and contemporary chronicles were full of lamentations at the degeneracy of the times. Some excellent bishops there were during the fourteenth century, notably Fraser and Lamberton of St. Andrews, the former of whom was chosen one of the regents of the kingdom, while Lamberton completed the noble cathedral of St. Andrews. Bishop David of Moray, a zealous patron of learning, is honoured as the virtual founder of the historic Scots College in Paris. A proof that religious zeal was still warm is afforded by the first foundation in Scotland, at Dunbar, of a collegiate church, in 1342, precursor of some forty other establishments of the same kind founded before the Reformation.

David II died childless, and the first of the long line of Stuart kings now ascended the throne in the person of Robert, son of Marjorie (daughter of Robert Bruce) and the High Steward. During Robert's reign of nineteen years there was almost continual warfare with the English on the Border, France on one occasion sending a force to help her Scottish ally against their common enemy. Robert was succeeded in 1390 by his son Robert III, in whose reign Scotland suffered more from its own turbulent barons than from foreign foes. Robert, Duke of Albany, the king's brother, himself wielded almost royal power, imprisoned and (it was said) starved to death the heir-apparent to the throne; and when the king died in 1466, leaving his surviving son James a prisoner in England, Albany got himself appointed regent, and did his best to prevent the new king's return to Scotland. The years of Albany's dictatorship, which coincided with the general unrest in Christendom due to a disputed papal election, were not prosperous ones for the Scottish Church. Spiritual authority was weakened, and the encroachments of the State on the Church became increasingly serious. A collection of synodal statutes of St. Andrews, however, of this date which has come down to us shows that serious efforts were being made by the church authorities to cope with the evils of the time ; and the long alliance with France of course brought the French and Scottish churches into a close connection which was in many ways advantageous, although one effect of it was that Scotland, like France, espoused the cause of the antipopes against the rightful pontiffs. The young king, James I, was at length released from England in 1424, after twenty years' captivity, returned to his realm; immediately showed himself a strong and gifted monarch. He condemned Albany and his two sons to death for high treason, took vigorous steps to improve and encourage commerce and trade, and evinced the greatest interest in the welfare of religion and the prosperity of the Church. The Parliament of 1425 directed a strict Inquisition into the spread of Lollardism or other heresies, and the punishment of those who disseminated them; and James also personally urged the heads of the religious orders in his realm to see to a stricter observance of their rule and discipline. The king sent eight high Scottish ecclesiastics to Basle to attend the general council there; but in the midst of his plans of reform he was assassinated at Perth in February, 1436.

King James's solicitude as to the spread of heresy in Scotland was not without cause; for early in his reign preachers of the Wyclifite errors had come from England, prominent among them being John Resby, who was sentenced to death and suffered at Perth in 1407. The Scottish Parliament passed a special act against Lollardism in 1425; and Paul Crawar, an emissary from the Hussites of Bohemia, who appeared in Scotland on a proselytizing mission in 1433, suffered the same fate as Resby. An oath to defend the Church against Lollardism was taken by all graduates of the new University of St. Andrews , the foundation of which was a notable event of this reign. It was formally confirmed in 1414 by Pedro de Luna, recognized by the Scottish Church at that time as Pope Benedict XIII. Scotland was the last state in Christendom to adhere to the antipope, and only in 1418 declared her allegiance to the rightful pontiff, Martin V . The year before his death James received a visit from the learned and distinguished Æneas Sylvius Piccolomini, who afterwards became Pope Pius II. About the same time the new Diocese of the Isles was erected, being severed from that of Argyll; and the bishops of the new see fixed their residence at Iona.

The new king, James II, had a long minority, during which there were constant feuds among his nobles; but he developed at manhood into a firm and prudent ruler, and he was fortunate in having as an adviser Bishop Kennedy of St. Andrews, one of the wisest and best prelates who ever adorned that see. James's early death, owing to an accident, in 1460, was doubly unfortunate, as his son and successor James III was a prince of far weaker character, unable to cope with the turbulent barons, some of whom broke out into open revolt, seducing the youthful heir to the throne to join them. Active hostilities followed, and James was murdered by a trooper of the insurgent army in 1488. The disturbances of his reign had their effect on the Scottish Church, in which abuses, such as the intrusion of laymen into ecclesiastical positions, the deprival suffered by cathedral and monastic bodies of their canonical rights, and the baneful system of commendatory abbots, flourished almost unchecked. New religious foundations there were, chiefly of the orders of friars ; and the diocesan development of the Church was completed by the withdrawal of the See of Galloway from the jurisdiction of York, and those of Orkney and the Isles from Norway. This act of consolidation formed part of the provisions of an important Bull of Sixtus IV , dated 1472, erecting the See of St. Andrews into an archbishopric and metropolitan church for the whole realm, with twelve suffragan sees dependent on it. York and Trondhjem, of course, protested against the change; but it seemed to be equally unwelcome in Scotland. The new metropolitan, Archbishop Graham, found king, clergy, and people all against him; he was assailed by various serious charges, and finally deprived of his dignities, degraded from his orders, and sentenced to lifelong imprisonment in a monastery. His successor in the archbishopric, William Sheves, obtained a Bull from Innocent VIII appointing him primate of all Scotland and legatus natus , with the same privileges as those enjoyed by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The protest of the See of Glasgow was followed by a Bull exempting that see from the jurisdiction of the Primate, but in 1489 a law was passed declaring the necessity of Glasgow's being erected into an archbishopric. In 1492 the pope created the new archbishopric, assigning to it as suffragans the Sees of Dunkeld, Dunblane, Galloway, and Argyll. Two years later we hear of the arrest and trial of a number of Lollards in the new archdiocese ; but they seem to have escaped with an admonition. From 1497 to 1513 the primatial see was occupied successively by a brother and a natural son of King James IV. The latter, who was nominated to the primacy when only sixteen, fell with his royal father and the flower of the Scottish nobility at Plodden in 1513. Foreman, who succeeded him as archbishop, was an able and zealous prelate ; but by far the most distinguished Scottish bishop at this period was the learned and holy William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen 1483-1514, and founder of Aberdeen University in 1494.

In 1525 the Lutheran opinions seem first to have appeared in Scotland, the parliament of that year passing an act forbidding the importation of Lutheran books. James V was a staunch son of the Church, and wrote to Pope Clement VII in 1526, protesting his determination to resist every form of heresy. Patrick Hamilton a commendatory abbot and connected with the royal house, was tried and condemned for teaching false doctrine, and burned at St. Andrews in 1528; but his death, which Knox claims to have been the starting-point of the Reformation in Scotland, certainly did not stop the spread of the new opinions. James, whilst showing himself zealous for the reform of ecclesiastical abuses in his realm, resisted all the efforts of his uncle Henry VIII of England to draw him over to the new religion. He married the only daughter of the King of France in 1537, much to Henry's chagrin; but his young wife died within three months. Meanwhile his kingdom was divided into two opposing parties — one including many nobles, the queen-mother (sister of Henry VIII ), and the religiously disaffected among his subjects, secretly supporting Henry's schemes and the advance of the new opinions; the other, comprising the powerful and wealthy clergy, several peers of high rank, and the great mass of his still Catholic and loyal subjects. Severe measures continued against the disseminators of Lutheranism, many suffering death or banishment; and there were not wanting able and patriotic counsellors to stand by the king, notable among them being David Beaton , whom we find in France negotiating for the marriage of James to Mary of Guise in 1537, and himself uniting the royal pair at St. Andrews. Beaton became cardinal in 1538 and Primate of Scotland a few weeks later, on the death of his uncle James Beaton , and found himself the object of Henry VIII's jealousy and animosity, as the greatest obstacle to that monarch's plans and hopes. Henry's anger culminated on the bestowal by the pope on the King of Scots of the very title which he had himself received from Leo X ; open hostilities broke out, and shortly after the disastrous rout of the Scotch forces at Solway Moss in 1542 James V died at Falkland, leaving a baby daughter, Mary Stuart, to inherit his crown and the government of his distracted country.

James V's death was immediately followed by new activity on the part of the Protestant party. The Regent Arran openly favoured the new doctrines, and many of the Scottish nobles bound themselves, for a money payment from Henry VIII, to acknowledge him as lord paramount of Scotland. Beaton was imprisoned, a step which resulted in Scotland being placed under an interdict by the pope, whereupon the people, still in great part Catholic, insisted on the cardinal's release. Henry now connived at, if he did not actually originate, a plan for the assassination of Beaton, in which George Wishart, a conspicuous Protestant preacher was also mixed up. Wishart was tried for heresy and burned at St. Andrews in 1546, and two months later Beaton was murdered in the same city. Arran, who had meanwhile reverted to Catholicism, wrote to the pope deploring Beaton's death, asking for a subsidy toward the war with England. The Protestants held the Castle of St. Andrews, among them being John Knox ; and the fortress was only recovered by the aid of a French squadron. Disaffection and treachery were rife among the nobles, and the English Protector Somerset, secure of their support, led an English army over the border, and defeated the Scottish forces with great loss at Pinkie in 1547.

A few months later the young queen was sent by her mother, Mary of Guise, to France, which remained her home for thirteen years. The French alliance enabled Scotland to drive back her English invaders; peace was declared in 1550, Mary of Guise appointed regent in succession to the weak and vacillating Arran, entering on office just as a Catholic queen, Mary Tudor, was ascending the English throne. Arran's half-brother, John Hamilton, succeeded Beaton as Archbishop of St. Andrews, James Beaton soon after being appointed to Glasgow, while the See of Orkney was held by the pious, learned, and able Robert Reid, the virtual founder of Edinburgh University. The primate convoked a provincial national council in Edinburgh in 1549, at which sixty ecclesiastics were present. A series of important canons was passed at this council, as well as at a subsequent one assembled in 1552, one result being the publication in the latter year of a catechism intended for the instruction of the clergy as well as of their flocks. From 1547 to 1555 John Knox was preaching Protestantism in England, Geneva, and Frankfort

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

-

-

Mysteries of the Rosary

-

St. Faustina Kowalska

-

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

-

Saint of the Day for Wednesday, Oct 4th, 2023

-

Popular Saints

-

St. Francis of Assisi

-

Bible

-

Female / Women Saints

-

7 Morning Prayers you need to get your day started with God

-

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Thursday, November 21, 2024

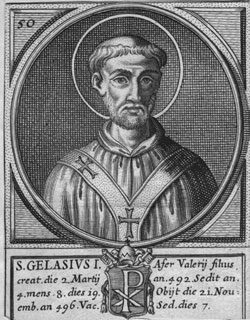

Daily Readings for Thursday, November 21, 2024 St. Gelasius: Saint of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024

St. Gelasius: Saint of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024 Act of Consecration to the Holy Spirit: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024

Act of Consecration to the Holy Spirit: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024- Daily Readings for Wednesday, November 20, 2024

- St. Edmund Rich: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, November 20, 2024

- Act of Adoration: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, November 20, 2024

![]()

Copyright 2024 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2024 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Thursday, November 21, 2024

Daily Readings for Thursday, November 21, 2024 St. Gelasius: Saint of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024

St. Gelasius: Saint of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024 Act of Consecration to the Holy Spirit: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024

Act of Consecration to the Holy Spirit: Prayer of the Day for Thursday, November 21, 2024