We ask you, urgently: don’t scroll past this

Dear readers, Catholic Online was de-platformed by Shopify for our pro-life beliefs. They shut down our Catholic Online, Catholic Online School, Prayer Candles, and Catholic Online Learning Resources—essential faith tools serving over 1.4 million students and millions of families worldwide. Our founders, now in their 70's, just gave their entire life savings to protect this mission. But fewer than 2% of readers donate. If everyone gave just $5, the cost of a coffee, we could rebuild stronger and keep Catholic education free for all. Stand with us in faith. Thank you.Help Now >

The Sacrament of Penance

FREE Catholic Classes

Penance is a sacrament of the New Law instituted by Christ in which forgiveness of sins committed after baptism is granted through the priest's absolution to those who with true sorrow confess their sins and promise to satisfy for the same. It is called a "sacrament" not simply a function or ceremony, because it is an outward sign instituted by Christ to impart grace to the soul. As an outward sign it comprises the actions of the penitent in presenting himself to the priest and accusing himself of his sins, and the actions of the priest in pronouncing absolution and imposing satisfaction. This whole procedure is usually called, from one of its parts, "confession", and it is said to take place in the "tribunal of penance", because it is a judicial process in which the penitent is at once the accuser, the person accused, and the witness, while the priest pronounces judgment and sentence. The grace conferred is deliverance from the guilt of sin and, in the case of mortal sin, from its eternal punishment; hence also reconciliation with God, justification. Finally, the confession is made not in the secrecy of the penitent's heart nor to a layman as friend and advocate, nor to a representative of human authority, but to a duly ordained priest with requisite jurisdiction and with the " power of the keys ", i.e., the power to forgive sins which Christ granted to His Church.

By way of further explanation it is needful to correct certain erroneous views regarding this sacrament which not only misrepresent the actual practice of the Church but also lead to a false interpretation of theological statement and historical evidence. From what has been said it should be clear:

- that penance is not a mere human invention devised by the Church to secure power over consciences or to relieve the emotional strain of troubled souls ; it is the ordinary means appointed by Christ for the remission of sin. Man indeed is free to obey or disobey, but once he has sinned, he must seek pardon not on conditions of his own choosing but on those which God has determined, and these for the Christian are embodied in the Sacrament of Penance.

- No Catholic believes that a priest simply as an individual man, however pious or learned, has power to forgive sins. This power belongs to God alone; but He can and does exercise it through the ministration of men. Since He has seen fit to exercise it by means of this sacrament, it cannot be said that the Church or the priest interferes between the soul and God ; on the contrary, penance is the removal of the one obstacle that keeps the soul away from God.

- It is not true that for the Catholic the mere "telling of one's sins " suffices to obtain their forgiveness. Without sincere sorrow and purpose of amendment, confession avails nothing, the pronouncement of absolution is of no effect, and the guilt of the sinner is greater than before.

- While this sacrament as a dispensation of Divine mercy facilitates the pardoning of sin, it by no means renders sin less hateful or its consequences less dreadful to the Christian mind ; much less does it imply permission to commit sin in the future. In paying ordinary debts, as e.g., by monthly settlements, the intention of contracting new debts with the same creditor is perfectly legitimate; a similar intention on the part of him who confesses his sins would not only be wrong in itself but would nullify the sacrament and prevent the forgiveness of sins then and there confessed.

- Strangely enough, the opposite charge is often heard, viz., that the confession of sin is intolerable and hard and therefore alien to the spirit of Christianity and the loving kindness of its Founder. But this view, in the first place, overlooks the fact that Christ, though merciful, is also just and exacting. Furthermore, however painful or humiliating confession may be, it is but a light penalty for the violation of God's law. Finally, those who are in earnest about their salvation count no hardship too great whereby they can win back God's friendship.

The Council of Trent (1551) declares:

As a means of regaining grace and justice, penance was at all times necessary for those who had defiled their souls with any mortal sin. . . . Before the coming of Christ, penance was not a sacrament, nor is it since His coming a sacrament for those who are not baptized. But the Lord then principally instituted the Sacrament of Penance, when, being raised from the dead, he breathed upon His disciples saying: 'Receive ye the Holy Ghost. Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them; and whose sins you shall retain, they are retained' ( John 20:22-23 ). By which action so signal and words so clear the consent of all the Fathers has ever understood that the power of forgiving and retaining sins was communicated to the Apostles and to their lawful successors, for the reconciling of the faithful who have fallen after Baptism. (Sess. XIV, c. i)Farther on the council expressly states that Christ left priests, His own vicars, as judges ( praesides et judices ), unto whom all the mortal crimes into which the faithful may have fallen should be revealed in order that, in accordance with the power of the keys , they may pronounce the sentence of forgiveness or retention of sins " (Sess. XIV, c. v)

Power to Forgive SinsIt is noteworthy that the fundamental objection so often urged against the Sacrament of Penance was first thought of by the Scribes when Christ said to the sick man of the palsy: "Thy sins are forgiven thee." "And there were some of the scribes sitting there, and thinking in their hearts: Why doth this man speak thus? he blasphemeth. Who can forgive sins but God only?" But Jesus seeing their thoughts, said to them: "Which is easier to say to the sick of the palsy: Thy sins are forgiven thee; or to say, Arise, take up thy bed and walk? But that you may know that the Son of man hath power on earth to forgive sins, (he saith to the sick of the palsy,) I say to thee: Arise, take up thy bed, and go into thy house" ( Mark 2:5-11 ; Matthew 9:2-7 ). Christ wrought a miracle to show that He had power to forgive sins and that this power could be exerted not only in heaven but also on earth. This power, moreover, He transmitted to Peter and the other Apostles. To Peter He says: "And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven : and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven " ( Matthew 16:19 ). Later He says to all the Apostles : "Amen I say to you, whatsoever you shall bind upon earth, shall be bound also in heaven ; and whatsoever you shall loose upon earth, shall be loosed also in heaven " ( Matthew 18:18 ). As to the meaning of these texts, it should be noted:

- that the "binding" and "loosing" refers not to physical but to spiritual or moral bonds among which sin is certainly included; the more so because

- the power here granted is unlimited -- " whatsoever you shall bind, . . . whatsoever you shall loose";

- the power is judicial, i.e., the Apostles are authorized to bind and to loose ;

- whether they bind or loose, their action is ratified in heaven. In healing the palsied man Christ declared that "the Son of man has power on earth to forgive sins "; here He promises that what these men, the Apostles, bind or loose on earth, God in heaven will likewise bind or loose. (Cf. also POWER OF THE KEYS.)

- Christ here reiterates in the plainest terms -- " sins ", "forgive", "retain" -- what He had previously stated in figurative language, "bind" and "loose", so that this text specifies and distinctly applies to sin the power of loosing and binding.

- He prefaces this grant of power by declaring that the mission of the Apostles is similar to that which He had received from the Father and which He had fulfilled: "As the Father hath sent me". Now it is beyond doubt that He came into the world to destroy sin and that on various occasions He explicitly forgave sin ( Matthew 9:2-8 ; Luke 5:20 ; 7:47 ; Revelation 1:5 ), hence the forgiving of sin is to be included in the mission of the Apostles.

- Christ not only declared that sins were forgiven, but really and actually forgave them; hence, the Apostles are empowered not merely to announce to the sinner that his sins are forgiven but to grant him forgiveness-"whose sins you shall forgive". If their power were limited to the declaration " God pardons you", they would need a special revelation in each case to make the declaration valid.

- The power is twofold -- to forgive or to retain, i.e., the Apostles are not told to grant or withhold forgiveness nondiscriminately; they must act judicially, forgiving or retaining according as the sinner deserves.

- The exercise of this power in either form (forgiving or retaining) is not restricted: no distinction is made or even suggested between one kind of sin and another, or between one class of sinners and all the rest: Christ simply says "whose sins ".

- The sentence pronounced by the Apostles (remission or retention) is also God's sentence -- "they are forgiven . . . they are retained".

These pronouncements were directed against the Protestant teaching which held that penance was merely a sort of repeated baptism ; and as baptism effected no real forgiveness of sin but only an external covering over of sin through faith alone, the same, it was alleged, must be the case with penance. This, then, as a sacrament is superfluous; absolution is only a declaration that sin is forgiven through faith, and satisfaction is needless because Christ has satisfied once for all men. This was the first sweeping and radical denial of the Sacrament of Penance. Some of the earlier sects had claimed that only priests in the state of grace could validly absolve, but they had not denied the existence of the power to forgive. During all the preceding centuries, Catholic belief in this power had been so clear and strong that in order to set it aside Protestantism was obliged to strike at the very constitution of the Church and reject the whole content of Tradition.

Belief and Practice of the Early ChurchAmong the modernistic propositions condemned by Pius X in the Decree "Lamentabili sane" (3 July, 1907) are the following:

- "In the primitive Church there was no concept of the reconciliation of the Christian sinner by the authority of the Church, but the Church by very slow degrees only grew accustomed to this concept. Moreover, even after penance came to be recognized as an institution of the Church, it was not called by the name of sacrament, because it was regarded as an odious sacrament." (46)

- "The Lord's words: 'Receive ye the Holy Ghost, whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them, and whose sins you shall retain they are retained' (John xx, 22-23), in no way refer to the Sacrament of Penance, whatever the Fathers of Trent may have been pleased to assert." (47)

Turning now to evidence of a positive sort, we have to note that the statements of any Father or orthodox ecclesiastical writer regarding penance present not merely his own personal view, but the commonly accepted belief ; and furthermore that the belief which they record was no novelty at the time, but was the traditional doctrine handed down by the regular teaching of the Church and embodied in her practice. In other words, each witness speaks for a past that reaches back to the beginning, even when he does not expressly appeal to tradition.

- St. Augustine (d. 430) warns the faithful: "Let us not listen to those who deny that the Church of God has power to forgive all sins " (De agon. Christ., iii).

- St. Ambrose (d. 397) rebukes the Novatianists who "professed to show reverence for the Lord by reserving to Him alone the power of forgiving sins. Greater wrong could not be done than what they do in seeking to rescind His commands and fling back the office He bestowed. . . . The Church obeys Him in both respects, by binding sin and by loosing it; for the Lord willed that for both the power should be equal" (De poenit., I, ii,6).

- Again he teaches that this power was to be a function of the priesthood. "It seemed impossible that sins should be forgiven through penance; Christ granted this (power) to the Apostles and from the Apostles it has been transmitted to the office of priests " (op. cit., II, ii, 12).

- The power to forgive extends to all sins : " God makes no distinction; He promised mercy to all and to His priests He granted the authority to pardon without any exception " (op. cit., I, iii, 10).

- Against the same heretics St. Pacian, Bishop of Barcelona (d. 390), wrote to Sympronianus, one of their leaders: "This (forgiving sins ), you say, only God can do. Quite true : but what He does through His priests is the doing of His own power" (Ep. I ad Sympron, 6 in P.L., XIII, 1057).

- In the East during the same period we have the testimony of St. Cyril of Alexandria (d. 447): "Men filled with the spirit of God (i.e. priests ) forgive sins in two ways, either by admitting to baptism those who are worthy or by pardoning the penitent children of the Church " (In Joan., 1, 12 in P.G., LXXIV, 722).

- St. John Chrysostom (d. 407) after declaring that neither angels nor archangels have received such power, and after showing that earthly rulers can bind only the bodies of men, declares that the priest's power of forgiving sins "penetrates to the soul and reaches up to heaven ". Wherefore, he concludes, "it were manifest folly to condemn so great a power without which we can neither obtain heaven nor come to the fulfillment of the promises. . . . Not only when they (the priests ) regenerate us ( baptism ), but also after our new birth, they can forgive us our sins " (De sacred., III, 5 sq.).

- St. Athanasius (d. 373): "As the man whom the priest baptizes is enlightened by the grace of the Holy Ghost, so does he who in penance confesses his sins, receive through the priest forgiveness in virtue of the grace of Christ " (Frag. contra Novat. in P. G., XXVI, 1315).

The distinction between sins that could be forgiven and others that could not, originated in the latter half of the second century as the doctrine of the Montanists, and especially of Tertullian. While still a Catholic, Tertullian wrote (A.D. 200-6) his "De poenitentia" in which he distinguishes two kinds of penance, one as a preparation for baptism, the other to obtain forgiveness of certain grievous sins committed after baptism, i.e., apostasy, murder, and adultery. For these, however, he allows only one forgiveness: "Foreseeing these poisons of the Evil One, God, although the gate of forgiveness has been shut and fastened up with the bar of baptism, has permitted it still to stand somewhat open. In the vestibule He has stationed a second repentance for opening to such as knock; but now once for all, because now for the second time; but never more, because the last time it had been in vain. . . . However, if any do incur the debt of a second repentance, his spirit is not to be forthwith cut down and undermined by despair. Let it be irksome to sin again, but let it not be irksome to repent again; let it be irksome to imperil oneself again, but let no one be ashamed to be set free again. Repeated sickness must have repeated medicine " (De poen., VII). Tertullian does not deny that the Church can forgive sins ; he warns sinners against relapse, yet exhorts them to repent in case they should fall. His attitude at the time was not surprising, since in the early days the sins above mentioned were severely dealt with; this was done for disciplinary reasons, not because the Church lacked power to forgive.

In the minds, however, of some people the idea was developing that not only the exercise of the power but the power itself was limited. Against this false notion Pope Callistus (218-22) published his "peremptory edict" in which he declares: "I forgive the sins both of adultery and of fornication to those who have done penance." Thereupon Tertullian, now become a Montanist, wrote his "De pudicitia" (A. D. 217-22). In this work he rejects without scruple what he had taught as a Catholic : "I blush not at an error which I have cast off because I am delighted at being rid of it . . . one is not ashamed of his own improvement." The " error " which he imputes to Callistus and the Catholics was that the Church could forgive all sins : this, therefore, was the orthodox doctrine which Tertullian the heretic denied. In place of it he sets up the distinction between lighter sins which the bishop could forgive and more grievous sins which God alone could forgive. Though in an earlier treatise, "Scorpiace", he had said (c. x) that "the Lord left here to Peter and through him to the Church the keys of heaven " he now denies that the power granted to Peter had been transmitted to the Church, i.e., to the numerus episcoporum or body of bishops. Yet he claims this power for the "spirituals" ( pneumatici ), although these, for prudential reasons, do not make use of it. To the arguments of the "Psychici", as he termed the Catholics, he replies: "But the Church, you say, has the power to forgive sin. This I, even more than you, acknowledge and adjudge. I who in the new prophets have the Paraclete saying: 'The Church can forgive sin, but I will not do that (forgive) lest they (who are forgiven) fall into other sins " (De pud., XXI, vii). Thus Tertullian, by the accusation which he makes against the pope and by the restriction which he places upon the exercise of the power of forgiving sin, bears witness to the existence of that power in the Church which he had abandoned.

Not content with assailing Callistus and his doctrine, Tertullian refers to the "Shepherd" ( Pastor ), a work written A.D. 140-54, and takes its author Hermas to task for favouring the pardon of adulterers. In the days of Hermas there was evidently a school of rigorists who insisted that there was no pardon for sin committed after baptism (Simil. VIII, vi). Against this school the author of the "Pastor" takes a resolute stand. He teaches that by penance the sinner may hope for reconciliation with God and with the Church. "Go and tell all to repent and they shall live unto God. Because the Lord having had compassion, has sent me to give repentance to all men, although some are not worthy of it on account of their works" (Simil. VIII, ii). Hermas, however, seems to give but one opportunity for such reconciliation, for in Mandate IV, i, he seems to state categorically that "there is but one repentance for the servants of God ", and further on in c. iii he says the Lord has had mercy on the work of his hands and hath set repentance for them; "and he has entrusted to me the power of this repentance. And therefore I say to you, if any one has sinned. . he has opportunity to repent once". Repentance is therefore possible at least once in virtue of a power vested in the priest of God. That Hermas here intends to say that the sinner could be absolved only once in his whole life is by no means a necessary conclusion. His words may well be understood as referring to public penance (see below) and as thus understood they imply no limitation on the sacramental power itself. The same interpretation applies to the statement of Clement of Alexandria (d. circa A.D. 215): "For God being very merciful has vouchsafed in the case of those who, though in faith, have fallen into transgression, a second repentance, so that should anyone be tempted after his calling, he may still receive a penance not to be repented of" (Stromata, II, xiii).

The existence of a regular system of penance is also hinted at in the work of Clement, "Who is the rich man that shall be saved?", where he tells the story of the Apostle John and his journey after the young bandit. John pledged his word that the youthful robber would find forgiveness from the Saviour; but even then a long serious penance was necessary before he could be restored to the Church. And when Clement concludes that "he who welcomes the angel of penance . . . will not be ashamed when he sees the Saviour", most commentators think he alludes to the bishop or priest who presided over the ceremony of public penance. Even earlier, Dionysius of Corinth (d. circa A.D. 17O), setting himself against certain growing Marcionistic traditions, taught not only that Christ has left to His Church the power of pardon, but that no sin is so great as to be excluded from the exercise of that power. For this we have the authority of Eusebius, who says (Hist. eccl., IV, xxiii): "And writing to the Church which is in Amastris, together with those in Pontus, he commands them to receive those who come back after any fall, whether it be delinquency or heresy ".

The "Didache" (q.v.) written at the close of the first century or early in the second, in IV, xiv, and again in XIV, i, commands an individual confession in the congregation: "In the congregation thou shalt confess thy transgressions"; or again: "On the Lord's Day come together and break bread . . . having confessed your transgressions that your sacrifice may be pure." Clement I (d. 99) in his epistle to the Corinthians not only exhorts to repentance, but begs the seditious to "submit themselves to the presbyters and receive correction so as to repent" (c. lvii), and Ignatius of Antioch at the close of the first century speaks of the mercy of God to sinners, provided they return" with one consent to the unity of Christ and the communion of the bishop ". The clause "communion of the bishop " evidently means the bishop with his council of presbyters as assessors. He also says (Ad Philadel,) "that the bishop presides over penance".

The transmission of this power is plainly expressed in the prayer used at the consecration of a bishop as recorded in the Canons of Hippolytus : "Grant him, 0 Lord, the episcopate and the spirit of clemency and the power to forgive sins " (c. xvii). Still more explicit is the formula cited in the "Apostolic Constitutions" (q.v.): "Grant him, 0 Lord almighty, through Thy Christ, the participation of Thy Holy Spirit, in order that he may have the power to remit sins according to Thy precept and Thy command, and to loosen every bond, whatsoever it be, according to the power which Thou hast granted to the Apostles." (Const. Apost., VIII, 5 in P. (i., 1. 1073). For the meaning of "episcopus", "sacerdos", "presbyter", as used in ancient documents, see BISHOP; HIERARCHY.

Exercise of the PowerThe granting by Christ of the power to forgive sins is the first essential of the Sacrament of Penance; in the actual exercise of this power are included the other essentials. The sacrament as such and on its own account has a matter and a form and it produces certain effects; the power of the keys is exercised by a minister (confessor) who must possess the proper qualifications, and the effects are wrought in the soul of the recipient, i.e., the penitent who with the necessary dispositions must perform certain actions (confession, satisfaction).

Matter and FormAccording to St. Thomas (Summa, III, lxxiv, a. 2) "the acts of the penitent are the proximate matter of this sacrament ". This is also the teaching of Eugenius IV in the "Decretum pro Armenis" ( Council of Florence , 1439) which calls the act's " quasi materia " of penance and enumerates them as contrition, confession, and satisfaction ( Denzinger -Bannwart, "Enchir.", 699). The Thomists in general and other eminent theologians, e.g., Bellarmine, Toletus, Francisco Suárez, and De Lugo, hold the same opinion. According to Scotus (In IV Sent., d. 16, q. 1, n. 7) "the Sacrament of Penance is the absolution imparted with certain words" while the acts of the penitent are required for the worthy reception of the sacrament. The absolution as an external ceremony is the matter, and, as possessing significant force, the form. Among the advocates of this theory are St. Bonaventure , Capreolus, Andreas Vega, and Maldonatus. The Council of Trent (Sess. XIV, c. 3) declares: "the acts of the penitent, namely contrition, confession, and satisfaction, are the quasi materia of this sacrament ". The Roman Catechism used in 1913 (II, v, 13) says: "These actions are called by the Council quasi materia not because they have not the nature of true matter, but because they are not the sort of matter which is employed externally as water in baptism and chrism in confirmation ". For the theological discussion see Palmieri, op. cit., p. 144 sqq.; Pesch, "Praelectiones dogmaticae", Freiburg, 1897; De San, "De poenitentia", Bruges, 1899; Pohle, "Lehrb. d. Dogmatik". Regarding the form of the sacrament, both the Council of Florence and the Council of Trent teach that it consists in the words of absolution. "The form of the Sacrament of penance, wherein its force principally consists, is placed in those words of the minister : "I absolve thee, etc."; to these words indeed, in accordance with the usage of Holy Church, certain prayers are laudably added, but they do not pertain to the essence of the form nor are they necessary for the administration of the sacrament " (Council of Trent, Sess. XIV, c. 3). Concerning these additional prayers, the use of the Eastern and Western Churches, and the question whether the form is deprecatory or indicative and personal, see ABSOLUTION. Cf. also the writers referred to in the preceding paragraph.

Effect"The effect of this sacrament is deliverance from sin " ( Council of Florence ). The same definition in somewhat different terms is given by the Council of Trent (Sess. XIV, c. 3): "So far as pertains to its force and efficacy, the effect ( res et effectus ) of this sacrament is reconciliation with God, upon which there sometimes follows, in pious and devout recipients, peace and calm of conscience with intense consolation of spirit". This reconciliation implies first of all that the guilt of sin is remitted, and consequently also the eternal punishment due to mortal sin. As the Council of Trent declares, penance requires the performance of satisfaction "not indeed for the eternal penalty which is remitted together with the guilt either by the sacrament or by the desire of receiving the sacrament, but for the temporal penalty which, as the Scriptures teach, is not always forgiven entirely as it is in baptism " (Sess. VI, c. 14). In other words baptism frees the soul not only from all sin but also from all indebtedness to Divine justice, whereas after the reception of absolution in penance, there may and usually does remain some temporal debt to be discharged by works of satisfaction (see below). "Venial sins by which we are not deprived of the grace of God and into which we very frequently fall are rightly and usefully declared in confession; but mention of them may, without any fault, be omitted and they can be expiated by many other remedies" (Council of Trent, Sess. XIV, c. 3). Thus, an act of contrition suffices to obtain forgiveness of venial sin, and the same effect is produced by the worthy reception of sacraments other than penance, e.g., by Holy Communion.

The reconciliation of the sinner with God has as a further consequence the revival of those merits which he had obtained before committing grievous sin. Good works performed in the state of grace deserve a reward from God, but this is forfeited by mortal sin, so that if the sinner should die unforgiven his good deeds avail him nothing. So long as he remains in sin, he is incapable of meriting : even works which are good in themselves are, in his case, worthless: they cannot revive, because they never were alive. But once his sin is cancelled by penance, he regains not only the state of grace but also the entire store of merit which had, before his sin, been placed to his credit. On this point theologians are practically unanimous: the only hindrance to obtaining reward is sin, and when this is removed, the former title, so to speak, is revalidated. On the other hand, if there were no such revalidation, the loss of merit once acquired would be equivalent to an eternal punishment, which is incompatible with the forgiveness effected by penance. As to the further question regarding the manner and extent of the revival of merit, various opinions have been proposed; but that which is generally accepted holds with Francisco Suárez (De reviviscentia meritorum) that the revival is complete, i.e., the forgiven penitent has to his credit as much merit as though he had never sinned. See De Augustinis, "De re sacramentaria", II, Rome, 1887; Pesch, op. cit., VII; Göttler, "Der hl. Thomas v. Aquin u. die vortridentinischen Thomisten über die Wirkungen d. Bussakramentes", Freiburg, 1904.

The Minister (i.e., the Confessor)From the judicial character of this sacrament it follows that not every member of the Church is qualified to forgive sins ; the administration of penance is reserved to those who are invested with authority. That this power does not belong to the laity is evident from the Bull of Martin V "Inter cunctas" (1418) which among other questions to be answered by the followers of Wyclif and Huss, has this: "whether he believes that the Christian. . . is bound as a necessary means of salvation to confess to a priest only and not to a layman or to laymen however good and devout" ( Denzinger -Bannwart, "Enchir.", 670). Luther's proposition, that "any Christian, even a woman or a child" could in the absence of a priest absolve as well as pope or bishop, was condemned (1520) by Leo X in the Bull "Exurge Domine" (Enchir., 753). The Council of Trent (Sess. XIV, c. 6) condemns as "false and as at variance with the truth of the Gospel all doctrines which extend the ministry of the keys to any others than bishops and priests, imagining that the words of the Lord ( Matthew 18:18 ; John 20:23 ) were, contrary to the institution of this sacrament, addressed to all the faithful of Christ in such wise that each and every one has the power of remitting sin ". The Catholic doctrine, therefore, is that only bishops and priests can exercise the power.

These decrees moreover put an end, practically, to the usage, which had sprung up and lasted for some time in the Middle Ages , of confessing to a layman in case of necessity. This custom originated in the conviction that he who had sinned was obliged to make known his sin to some one -- to a priest if possible, otherwise to a layman. In the work "On true penance and false" (De vera et falsa poenitentia), erroneously ascribed to St. Augustine, the counsel is given: "So great is the power of confession that if a priest be not at hand, let him (the person desiring to confess) confess to his neighbour." But in the same place the explanation is given: "although he to whom the confession is made has no power to absolve, nevertheless he who confesses to his fellow ( socio ) becomes worthy of pardon through his desire of confessing to a priest " (P. L., XL, 1113). Lea, who cites (I, 220) the assertion of the Pseudo-Augustine about confession to one's neighbour, passes over the explanation. He consequently sets in a wrong light a series of incidents illustrating the practice and gives but an imperfect idea of the theological discussion which it aroused. Though Albertus Magnus (In IV Sent., dist. 17, art. 58) regarded as sacramental the absolution granted by a layman while St. Thomas (IV Sent., d. 17, q. 3, a. 3, sol. 2) speaks of it as "quodammodo sacramentalis", other great theologians took a quite different view. Alexander of Hales (S

Join the Movement

When you sign up below, you don't just join an email list - you're joining an entire movement for Free world class Catholic education.

-

-

Mysteries of the Rosary

-

St. Faustina Kowalska

-

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

-

Saint of the Day for Wednesday, Oct 4th, 2023

-

Popular Saints

-

St. Francis of Assisi

-

Bible

-

Female / Women Saints

-

7 Morning Prayers you need to get your day started with God

-

Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Daily Catholic

Daily Readings for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

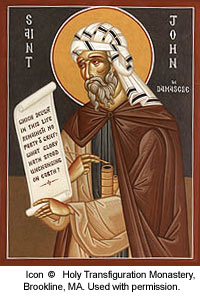

Daily Readings for Wednesday, December 04, 2024 St. John of Damascus: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

St. John of Damascus: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024 Thanks for Family and Friends: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

Thanks for Family and Friends: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024- Daily Readings for Tuesday, December 03, 2024

- St. Francis Xavier: Saint of the Day for Tuesday, December 03, 2024

- Prayer to Saint Therese De Lisieux for Guidance: Prayer of the Day for Tuesday, December 03, 2024

![]()

Copyright 2024 Catholic Online. All materials contained on this site, whether written, audible or visual are the exclusive property of Catholic Online and are protected under U.S. and International copyright laws, © Copyright 2024 Catholic Online. Any unauthorized use, without prior written consent of Catholic Online is strictly forbidden and prohibited.

Catholic Online is a Project of Your Catholic Voice Foundation, a Not-for-Profit Corporation. Your Catholic Voice Foundation has been granted a recognition of tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Federal Tax Identification Number: 81-0596847. Your gift is tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Daily Readings for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

Daily Readings for Wednesday, December 04, 2024 St. John of Damascus: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

St. John of Damascus: Saint of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024 Thanks for Family and Friends: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024

Thanks for Family and Friends: Prayer of the Day for Wednesday, December 04, 2024